Meet the North American Delegates to the RC General Convention

On April 29, 2024, delegates of the four Regnum Christi vocations from around the world will convene in Rome, Italy for the 2024 RC General Convention. The North American Territory will be sending 14 delegates, including three Consecrated Women of Regnum Christi, five Legionaries of Christ, and six lay members.

The assembled delegates will discern together the evangelizing focus of Regnum Christi for the next six years, in light of the current situation of the world and the needs of the Church, both locally and universally.

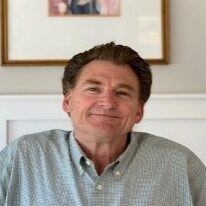

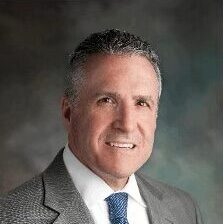

Around the world, input for this dialogue has been gathered at both the local and territorial level over the past year. Regnum Christi members of all vocations were encouraged to gather in teams to discuss the mission Regnum Christi is called to from their vantage point. This was collected in reports that were given to the 104 delegates of the RC Territorial Convention which was held in November 2023 in Chicago. At that Convention, five lay delegates were elected by the lay members present to represent them at the General Convention: Cathie Zentner, Donna Garrett, Tony Frese, Andrew Rawicki, and Horacio Gomez. Kerrie Rivard will also attend the General Convention ex-officio in her role as a lay member of the General Plenary Council over the last six years.

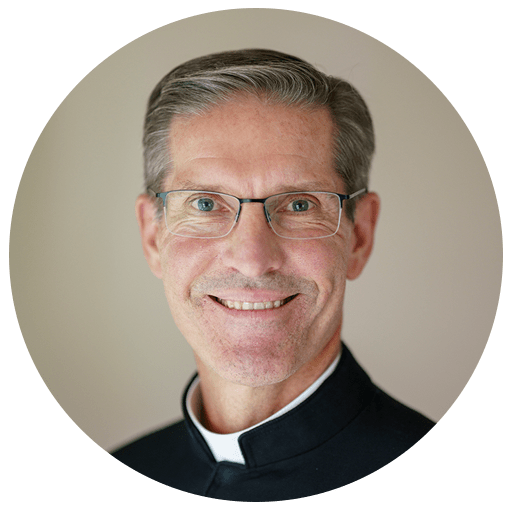

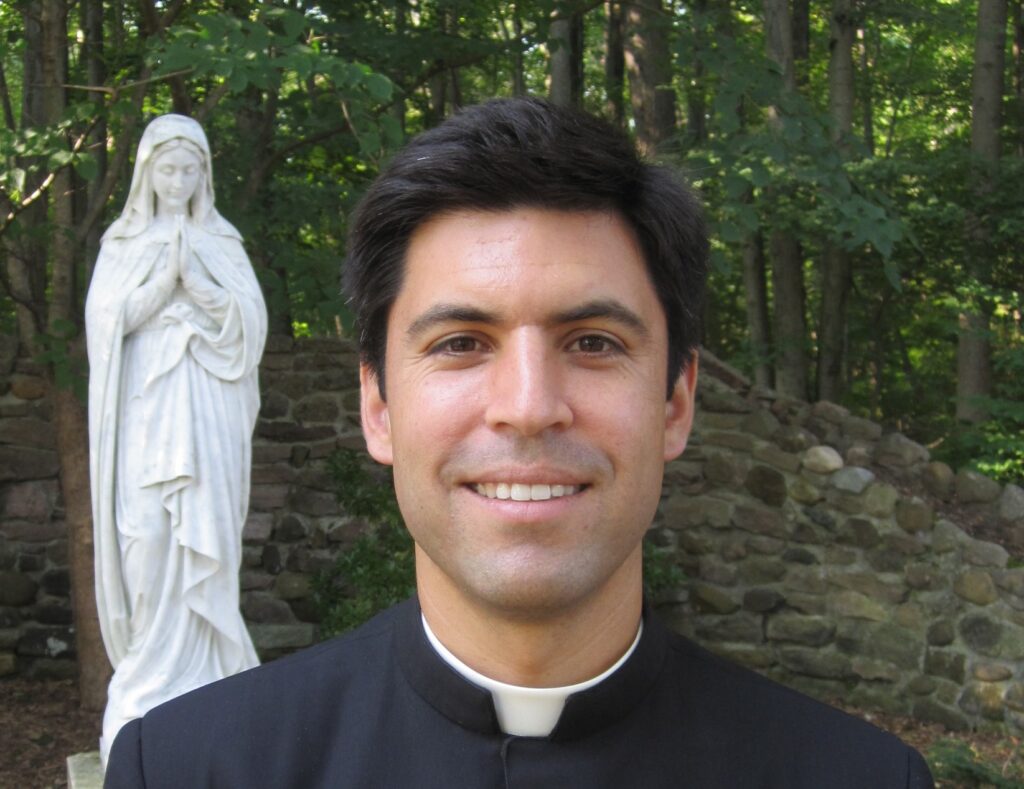

The Legionaries of Christ and the Consecrated Women of Regnum Christi both held elections to decide which members from the North American Territory would attend on their behalf. For the Legionaries, the delegates are: Fr. Shawn Aaron, Fr. John Bartunek, Fr. Bruce Wren, Fr. Juan Pablo Duran, and Fr. Lino Otero. The Consecrated Women will be represented by Kathleen Murphy, Helen Yalbir, and Maria Knuth.

Read the delegates’ bios by clicking on the photos below.

Consecrated Women of Regnum Christ

Meet the North American Delegates to the RC General Convention Read More »